What the Monetary Authorities Should Do

With CPI hitting a 40 year high of 9.1%, the Bank of England has responded by raising interest rates to 1.25%; up by 0.25 from the previous period. This, alongside ex chancellor and PM hopeful Rishi Sunak planning to ‘tackle inflation before tax cuts’, signals a poor plan for combating the rising effects of inflation.

Firstly inflation must be defined by its cause rather than its effect, in order for the monetary authorities to enact a sound policy of recovery. Inflation; in the truest sense, is an excess increase in the money supply over the real demand for money (MS > MD). MD; which is an inverse of velocity, is measured by the quantity of nominal pounds sterling economic actors hold over a period of time, in order to acquire a higher purchasing power for future consumption. Meaning individuals are withholding current consumption in preference of future consumption.

This time preference is an important concept, as it is the foundation of what makes interest possible. Other variables may effect interest rates; such as high risk or time till final settlement, but it is the time preference for future/current consumption which lays the foundation. Despite Milton Friedman’s wise words, inflation is not simply a monetary phenomenon, but a monetary and time phenomenon.

The time difference between the stages of production to consumption, alongside the furlough scheme during the 2020 covid outbreak, can help to better understand the financial cost and trade-off people now face, and what the monetary authorities should do.

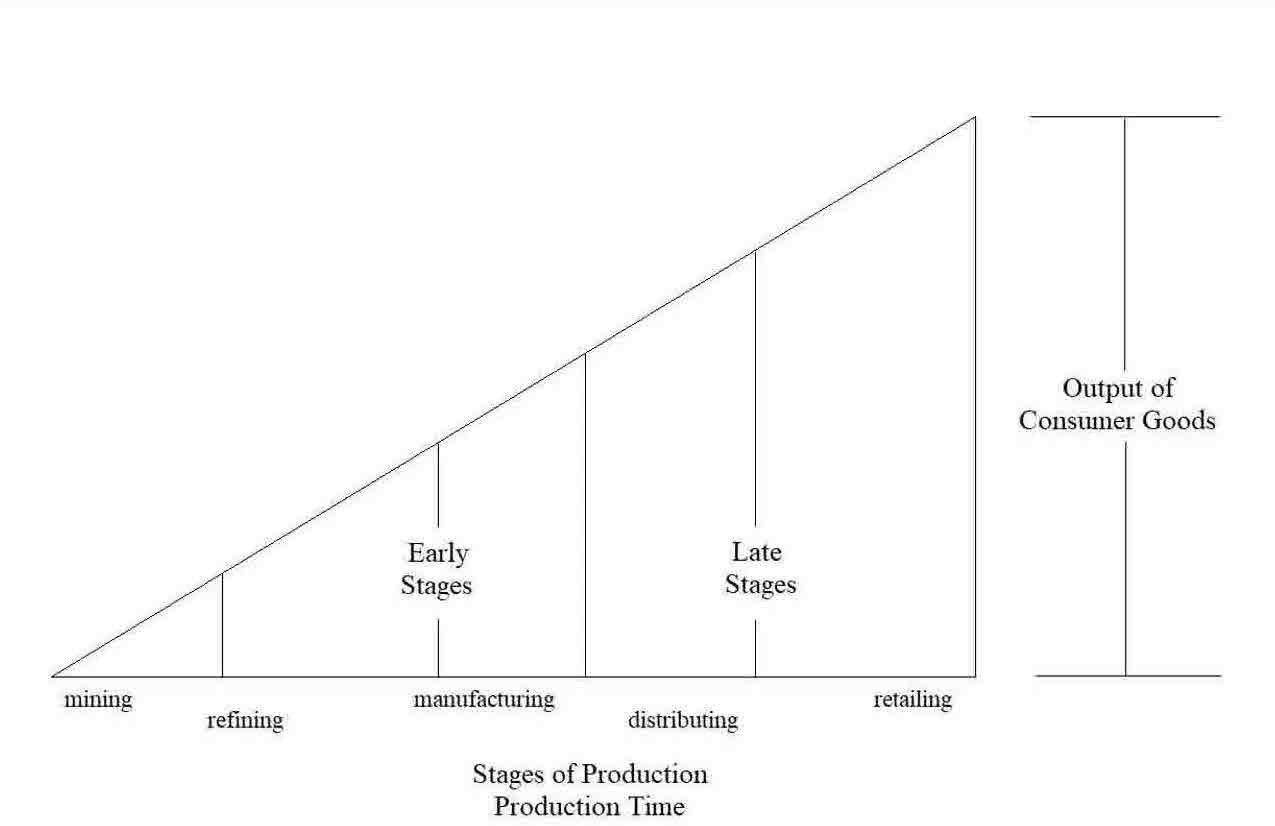

The Hayekian Triangle above denotes the stages and time process of production, where the production process is hypothesised as an input-output process; ‘the horizontal leg is representative of the production time, and the vertical leg is a measurement of the value of consumable outputs’ (Garrison, 2001).

As economic actors restrict their current consumption in favour of future consumption, a pooling of the social savings occurs. This results in a structural change in the multi-period production process, whereby the later stages of production face a contraction and the early stages face an expansion. This allows for the rate of interest to fall, as there are more financial resources available for loans, investment, and expansion.

By withholding from current consumption, earlier stages of production are permitted to expand, so consumers in the future will be able to consume more goods they value for a lower price.

This is what occurs under “normal” circumstances. Due to lockdowns and the furlough scheme however, distortions in the money and time market have been brought to bear.

Another way of looking at the nature of the high inflation rate, is that an excess of money has entered the economy faster than the production of goods and services.

This can be observed by returning to an adjusted Hayekian Triangle:

Here the darker triangle represents the production process during the covid outbreak and lockdown, and the scattered grey triangle represents current consumption. Due to the lockdown, production processes in many stages were halted, and with stimulus payments via furlough going to businesses to keep them afloat and to ensure workers could still receive pay without productivity, the money supply was increasing faster than production was growing, because production was immobilised.

So why are we only now feeling the effects of inflation?

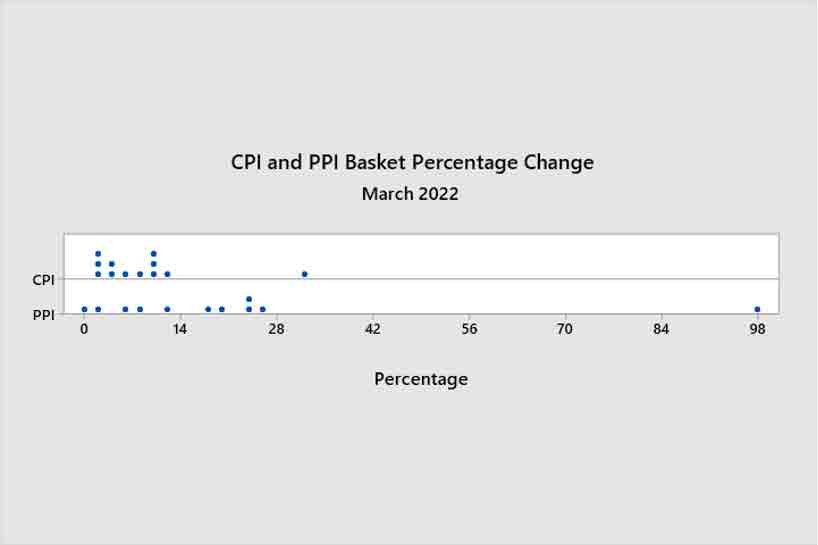

The distortion effects of inflation are not felt instantaneously, because money circulates through the economy at differing velocities for different sectors. This is why it is important not to only look at the average rate, but to look at all the price changes for the goods within the basket; this helps to identify where the excess money is circulating to-from, and how much.

Therefore not all price distortions will be the same; some will rise faster than others, some much slower; others may increase by larger percentages while goods valued less may increase by lower percentages.

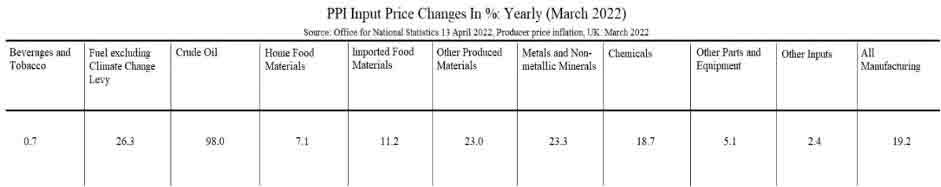

This is seen by looking at the basket of goods for the CPI and PPI input goods, from the report of March 2022:

As shown above, the most extreme changes in the CPI and PPI reports were 31.4% for housing and household services, and 98.0% for crude oil, with a range between the extreme upper and extreme lower for both being:

The average rate of change shown in CPI and PPI reports is the mean (x̄), and is calculated by adding the total % changes to one sum then dividing by the number of goods in the CPI and PPI baskets:

For the CPI:

For the PPI:

Furthermore we can visualise the spread of the price distortions by using a dotplot:

Getting back to the matter, the low rate policy of the Bank of England, and the remaining high tax rates are not effective policy measures for curbing the rising inflation.

The high tax rates leave consumers with less expendable income, meaning their cost of living is forced up and are less inclined to save. Moreover, government spending contributes to circulating excess money supply, and simply changes the makeup of our GDP. Instead of goods consumers want, we get more of what government wants; instead of more houses and petrol, we get more ditches being dug up to be refilled.

Additionally the low rate policy of the bank of England fails to address that the excess money is being spent faster than is being saved; a low rate of interest fails to reflect not only people’s expectation of higher inflation to come, but the preferences economic actors presently hold for current consumption.

So what should the monetary authorities do?

With the current rate of interest being 1.25%, adjusted for inflation the real rate is in the negative; as is calculated:

The Bank of England should aim to raise interest rates to a minimum of 13.5%, so as to ensure after adjusting for inflation, the real rate would not be in the negative, but would sit at 4.4%. This would help to properly signal that now is an appropriate time to save, and assist in incentivising the private sector into such actions. This would also, in principle, help curb incentives for banks looking to take high risk loans.

By increasing the interest rate to a nominal level of 13.5%, savers and investors will see there is a high demand, so as to allow earlier stages of production to expand for high levels of future output.

Additionally, the government should temporarily freeze VAT and sales tax in order to reduce the tax burden on consumers during the cost of living crises.

Finally, the government should temporarily freeze the capital gains tax until inflation is brought down to its target rate of 2%. This would ensure that investors receive 100% of their returns, providing a further incentive for large scale investments into expanding production processes and creating new, value inducing jobs.

The inflation and cost of living crises were created by large injections of money into the economy, and it is saving and investment that will help fix the distortions, by allowing for secular growth deflation.

Despite the Keynesian “paradox of thrift”, increased saving is not a decrease in economic activity, but a dynamic process that invests in a wider, more affordable future consumption.