‘Inflation’ is still transitory

I was wrong about both the persistence and magnitude of the price increases of goods and services. What did escape my reasoning, you ask? In short, I never thought banks and other credit institutions would be so stupid and reckless.

After a 16-month hiatus, I am getting back on the horse to resume analysing the economy and financial matters, as well as their prospects, of course.

In view of the fact that the “inflation” rate has been higher than the markets, Keynesian economists, most financial analysts and myself too had expected since I last dropped a line, I felt it was high time I reviewed my reasoning so as to find out what I missed.

Having said that, I must admit I was wrong about both the persistence and magnitude of the price increases of goods and services. What did escape my reasoning, you ask? In short, I never thought banks and other credit institutions would be so stupid and reckless as to open their spigots so damn hard and keep them open until now. Hence, the topic of today’s post is exactly this: the various factors that led to this relentless, but still transitory, “inflation”.

Since that last article on June 2021 was published, the rate at which prices in the real economy grow has reached levels not seen in a very long time nor in a manner as pervasive and all-encompassing as this. Afterall, developed countries, which will be the focus of this post, have not experienced these rates since the Great Inflation era that ended at the onset of the 1980’s. Ever since then, high “inflation” had only been a malaise afflicting the poorer, developing countries.

Before we continue, I have to remind the readers of the distinction between inflation and “inflation”. Basically, inflation is the expansion of the quantity of money and credit, which may cause an increase in prices in general, while “inflation” is the modern definition that means an increase of the general level of prices – check out the last link to see what is wrong with that definition and with actual inflation.

Moreover, according to Positive Economics (i.e., Keynesians, Monetarists, etc) – though we can just dub them all Keynesians seeing that, as Milton Friedman declared, “we are all Keynesian now” – a moderate pace of “inflation” is good because it is an indication that inflation is occurring and, therefore, this must mean more credit financing more business activity, consumption and investment. This is true. However, the consequences of the boom and bust cycle that this renders are disastrous, as the Austrian business cycle theory teaches.

Moving on to today’s agenda, to grasp this development, we ought to look at the demand and the supply sides separately. Beginning with demand, up until the end of the first half of 2021, the main factor on the demand side was government debt used to fund enormously profligate fiscal policies implemented in the advanced economies.

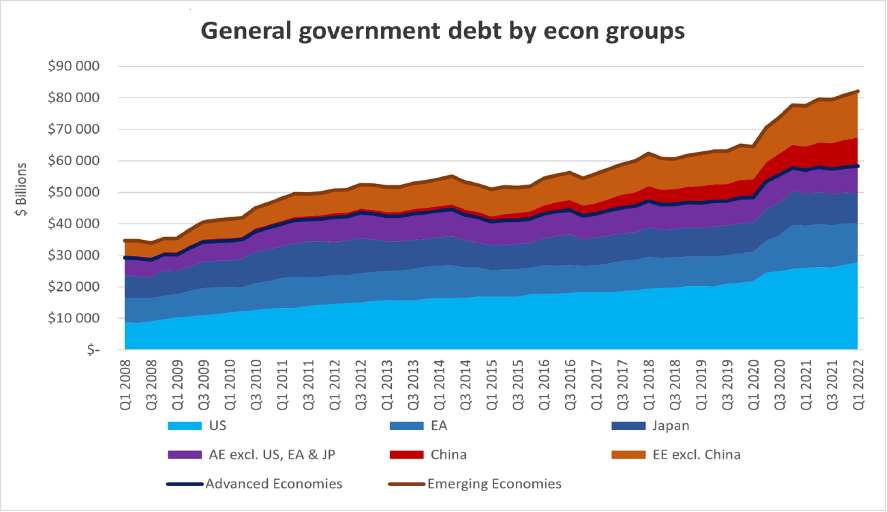

Like the following chart demonstrates, governments all around the world started showering their citizens with love in the form of financial aid. The most notorious one being direct contributions to individuals accounts or home addresses, more commonly referred as stimmy checks. As the name indicates, these were employed to, besides assisting those who had lost their jobs and were having difficulty making ends meet, stimulate consumption. In the Keynesian universe, this is necessary to maintain the economy at full-employment, whatever that level is – this is complete nonsense as you should know by now.

Unsurprisingly, Advanced Economies (AE) were more free-handed than the Emerging ones (EE). Because of the nature of the eurodollar system that favours the most liquid assets and financial instruments, which means the more reliable and predictable asset classes, owing to being the more creditworthy, AE spent more simply because they can.

At the same time, companies began looking for funding to pay their bills lest they downsize their payrolls. Obviously, governments provided a lot of that assistance. Nevertheless, due to the fickleness of political expediency, businesses leaned more to the financial sector. When the pandemic broke, suddenly companies tapped on their credit lines or begged for new ones, corporations issued a ton of bonds and banks and other credit providers – to avoid repetition, from now on, I will use these terms interchangeably – were more than willing to oblige.

If you recall, this experiment was supposed to have ended after a fortnight. It certainly should not have lasted two years. For assuming this interruption of our normal lives and of economic activity would be extremely ephemeral, and seeing that there was a tsunami of credit flowing out of financial centres and rushing into our shores, everybody became complaisant.

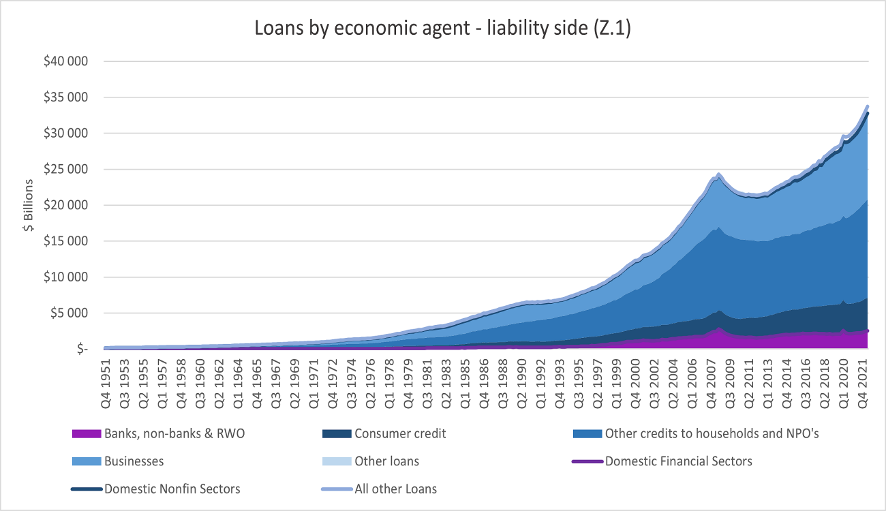

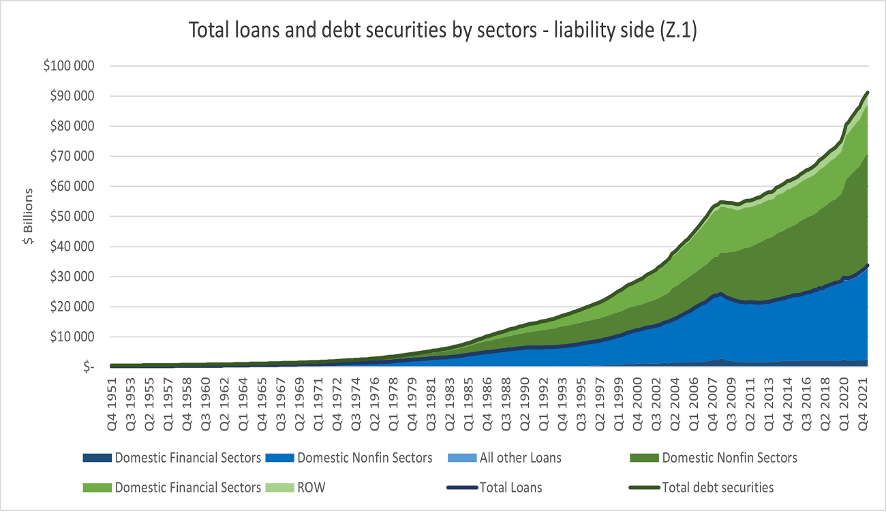

The case of the US is an excellent testament to this. If you pay close attention to the picture below, consumer credit jumped right at the onset of Covid, only to dwindle and then grow at a slower pace than the post-GFC average after that. Naturally, in view of consumers being awash in savings (i.e., stimmy checks), they had very little need do borrow to keep their indulgent lifestyles.

On the flip side, credit to businesses and mortgages (represented in the above graph as other credits to households and nonprofit organizations) shot up and continued to increase, though not at such a careless fashion. This has persisted until as recently as the first quarter of this year, for which we have the latest available data. As you will see, the short-sightedness of banks is the principal key, apart from governments (shown by the next chart), to explain our current situation regarding “inflation”, not the Fed.

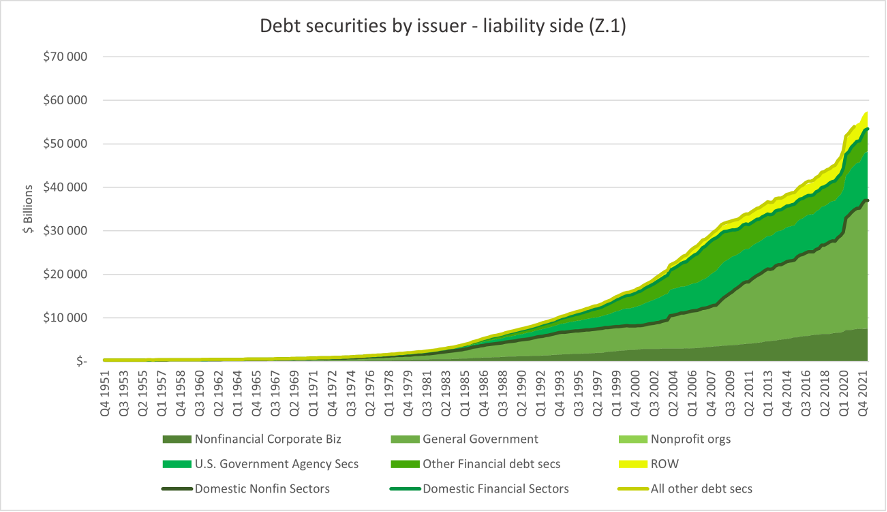

As I have already pointed out, companies accrued massive amounts of debt (also depicted in the following graph) to fund their operations. Be that as it may, they also had other objectives. Noticing that households were being inundated with money, industries started experiencing a tremendous surge in demand for their goods. The services sector only lately has felt this surge on their activity for obvious reasons.

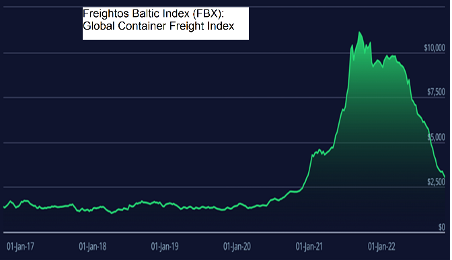

Therefore, a scramble for materials and intermediate goods to produce the final goods to retail, on the one hand, and a severely disrupted global supply chain on the other, resulted in the costs of production to skyrocket.

At a time when travel and trade became immensely hindered due to the restrictions imposed worldwide to allegedly fight the kung-flu, was when the western couch potatoes decided to binge on Amazon and ordering out with Uber Eats, Glovo or DoorDash.

To make matters worse, owing to the ultra-low or even negative interest rate environment, or in other words, the prudent behaviour of bankers facing prospects of low opportunities in this – do I dare say – disinflationary landscape, forced them to seek only the safest and most liquid investments. Thus, real estate became even more attractive, causing a rise in demand and, consequently, home builders intensified their activity. This is demonstrated in the previous chart, with US Government’s agency securities (i.e., mortgage-backed securities). As you ought to remember, lumber prices soared like never before, in part helped by obstacles in the normal functioning of sawmills and transportation.

In spite of the colossal elevation of transportation costs, as shown right above, the fact is that the economy has been adjusting, despite all the criminal Covid policies, and correcting the escalation of freight costs. Furthermore, compared to previous “inflationary” periods, this one just seems like a minor inconvenience.

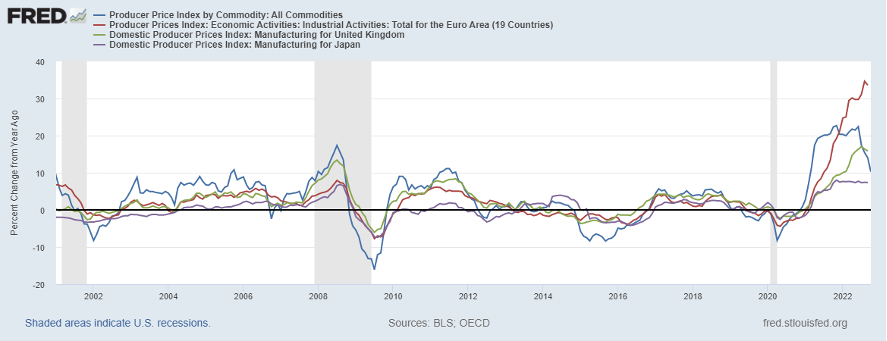

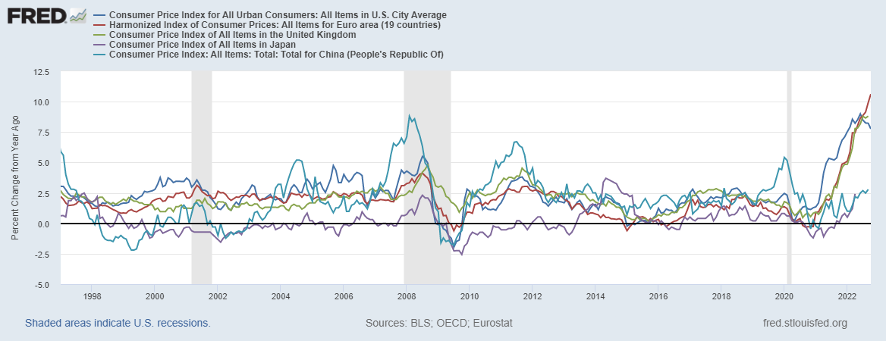

Although, to be fair, factoring all production costs, on average (PPIs shown top graph below), we have not lived through such a paradigm since the 1990’s, at least. Even the oil-induced “inflation” of the noughties did not rival with today.

Evidently, the surge in production costs had its effect on the PPI’s retail counterpart, the CPI (bottom chart). Still, the increase is limited by consumers’ purchasing power. Accordingly, since businesses have to stay competitive to keep and attract customers, they could not raise prices more intensely than their costs increase, resulting in consumer prices climbing at a slower pace than its producer analogue.

Indeed, consumption is a factor of production, more precisely of productivity, which means wages, and consumer credit. Picture a parallel reality where people focus on production and improving productivity to ameliorate their lot and raise their living standards, not only is this going to lead to reduced costs and falling prices (ceteris paribus, of course), but they will not have to be so irresponsible and keep on feeding this debt-based beast that goes by the name Eurodollar.

In a nutshell, instead of actual inflation, meaning an increase in the quantity of money and credit, in turn devaluing the currency, prices have increased at a higher rate chiefly because of a mismatch between demand and supply.

Albeit undeniable that debt went up, greasing the wheels of “inflation”, actually, the main culprits have been governments at first, followed by banks. On the first stage, from the beginning of the lockdowns in March 2020 till the second quarter of 2021, when the last and biggest round of stimmy checks were disbursed by the White House, governments had been the chief instigators. However, on the second stage, which I think has ended, banks took the baton and ran “inflation” to rates akin to the pre-GFC era.

Noticeably, the conflict between Russia and Ukraine has taken its toll on the global economy, constraining international trade and reducing the supply of vital commodities, such as crude oil, gas and wheat, thus affecting the costs of transportation and production. Besides the bellicose nature of the conflict, the hostilities encompassing economic and financial sanctions have added insult to injury. Notwithstanding, the impact has been limited to some geographies and it has mostly dissipated.

By looking at the exhibit above, total debt flowing through the American economy, at least the one captured by the government statistics, has recently evolved in a similar manner as the periods known as Great Inflation (began in the mid-1960’s and lasted up to 1982) and Great Moderation (started after the climax of the Great Inflation, and ended at the onset of the GFC, on August 9, 2007). As I have indicated, government spending was the trigger, which is clearly displayed by the jolt in the graph above (under the label Domestic Nonfinancial Sectors).

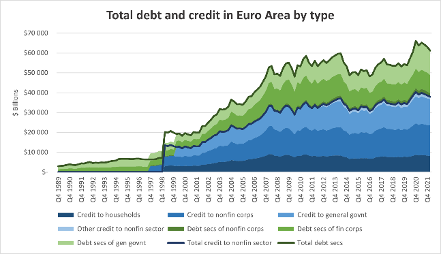

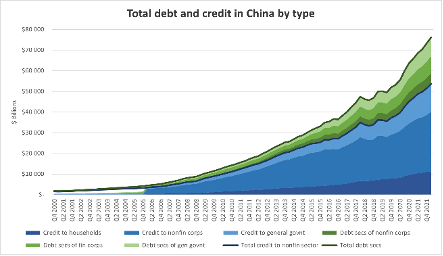

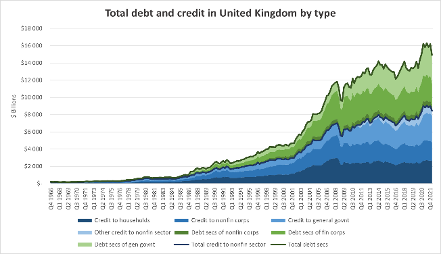

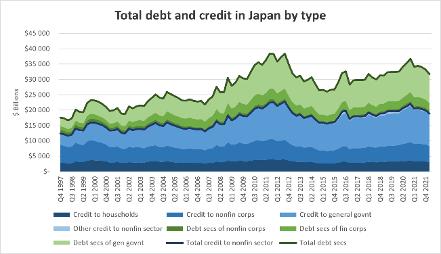

In addition, other countries have had an identical pattern as the US. Like I mentioned before, States extended their debts insofar as the markets gave them their blessings.

Interestingly, even though governments of the countries depicted above injected billions of euros, pounds and yens into their economies to kickstart growth and activity, banks did not get the memo and failed keep the momentum going. Besides their contractual obligations to provide open credit lines to their clients, banks have ostensibly been very heedful by trying to reduce their exposure. In fact, EA’s and Japan’s respective total debts both peaked in the fourth quarter of 2020, while the total debt of the UK climaxed in the second quarter of 2021, in spite of interest rates only starting to rise at the beginning of this year, as a reaction to increased expectations of rate hikes by the central bankers to control “inflation” – there is so much wrong with this reasoning that I am going to address it on another day.

Of those four countries/regions represented in the previous four graphs, only China has maintained an incessant pace of credit creation. Although every aggregate of economic agent class has increased borrowing, government has been the most profligate too, much like the US. Curiously, despite all this credit expansion, prices have not soared as much as in the West. The explanation has to be that the demand-supply imbalance did not become acute.

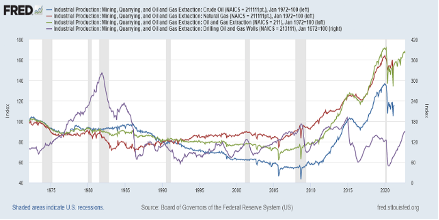

Moreover, oil and gas extraction or, more precisely, the lack of it has played a decisive role in the supply side of this demand-supply imbalance that has caused the “inflation” post-Covid. This topic deserves a post of its own, hence I will be succinct.

Whether you like it or not, fossil fuels – let’s just call it that, though I do not believe they come from fossils – provide the necessary energy to power the economy, even to fabricate and run wind power generators, solar panels or electrical vehicles. On that account, when they become scarce their prices jack up, rendering energy bills more expensive. Evidently, this means that individuals have a smaller space in their budgets for discretionary spending. In addition, this hampers businesses’ ability to produce, possibly even turning some ventures unfeasible. For this reason, companies may have to either reduce production and staff, or push the costs onto their clients in the form of higher prices. Keep this in mind.

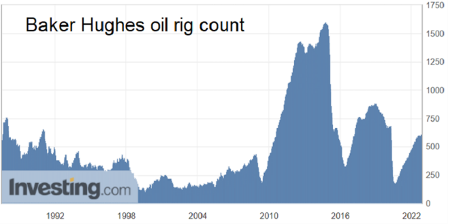

All the same, there is something I must indicate about the following couple of charts. The one on the left shows that oil and gas extraction is almost at pre-Covid levels, which means they are close to all-time highs. However, the Baker Hughes oil rig count hints at a totally different story. According to this indicator, active oil rigs in the US equal in amount those in the late 1980’s, when the count kicked off, and are well below those in 2014, when the fracking activity reached its zenith.

What I can surmise is that due to the “green” policies brought about by the anthropogenic climate change fraud, oil companies have been increasingly pressured to divest and encouraged to avoid further exploration. Regarding, the discrepancy between the two graphs, I take the view that it is a result of hedonic-quality adjustments, just like the CPI and GDP numbers go through. If the IP figures were accurately measured, I feel it would reflect the reality of much lower extraction and prospection activity.

Inside the oil and gas industry, refining has been constrained as well. The worsening refining bottleneck, especially in the US, was explained by Mike Wirth, the CEO of oil giant Chevron, who on June 3 of this year told Bloomberg TV that there’s not enough refining capacity to meet the demand for gasoline and diesel because no new refinery will ever be built in the US again.

The CEO Wirth explains his reason: “You’re looking at committing capital ten years out, that will need decades to offer a return for shareholders, in a policy environment where governments around the world are saying, ‘We don’t want these products to be used in the future.’”

Finally, after analysing the trajectory of banking activity and debt issuance, we have recognised Europe and Japan have been in the doldrums for more than a year, while the US and China have been the two main engines keeping the world economy afloat. In any case, to be honest, I think that if the CPI and GDP figures were precisely measures, with no hedonic adjustments or tampering with the weights, it would show that the whole globe is in a recession or worse. For the AE, especially Japan and European countries, I presume they have not even come close to reaching 2019 levels – of course, this inevitably makes us question if we ever bounced back from the Great Recession.

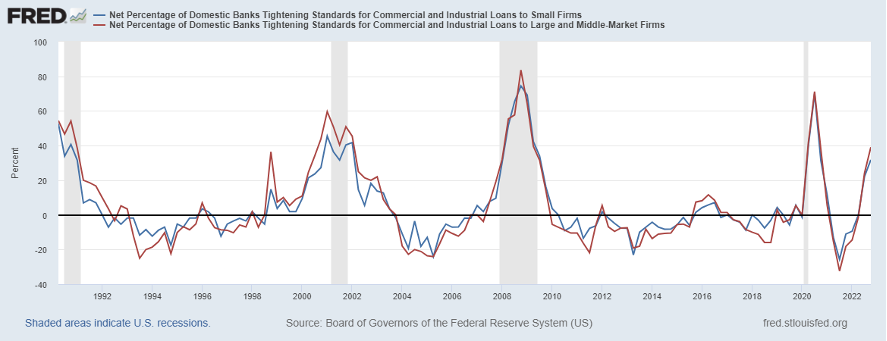

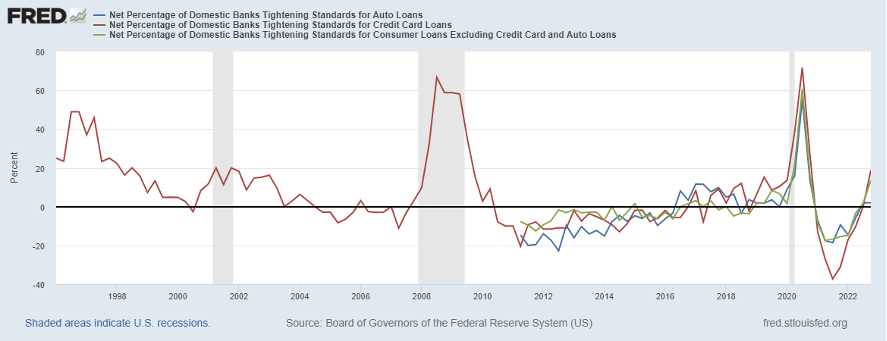

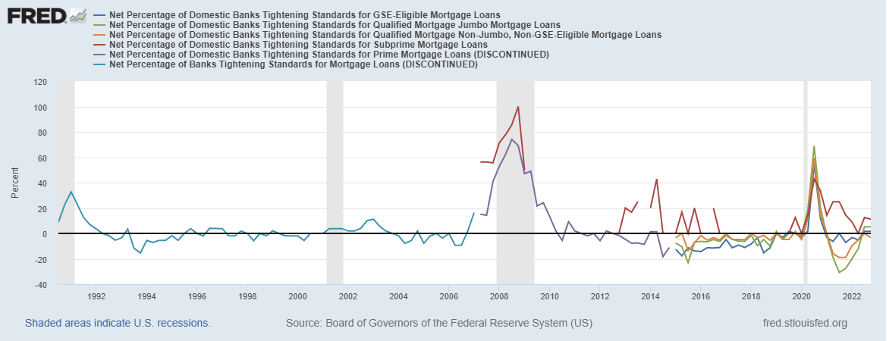

Apparently, since 2022 began, banks in the US have tightened their standards for giving out loans, whatever they may be. This is a plain attestation of the poor state of the economy, both businesses and households. Even the “primiest” prime mortgage loans are also being curtailed.

According to the Austrian business cycle theory, we are going through/towards a much needed and welcomed downturn to cure the malinvestments and distortions suffered in the last two years. Like a hangover that occurs after a night of recklessly gulping down alcohol, the body carries out its detox processes to get rid of the toxins and get your organism back to health.

Evidently, if we keep making that same mistake over and over again, or hinder the organism from executing the corrections necessary, then we are always going to be sick. Therefore, if governments continue to intervene on the economy whether it is to halt it or to boost demand beyond the capacity of the productive structure, they are going to destroy it, as well as the fabric of society.

To conclude, the escalation of prices is a symptom of a greater distress. During the pandemic, the structure of production suffered multiple blows, from the lack of workers that were better off staying unemployed to the heightened fuel and energy costs.

Unmistakably, this relentless meddling by bureaucrats and technocrats is rendering the future much more unpredictable. To make matters worse, geopolitical tensions and protectionist policies becoming trendy add to the uncertainty and to more inefficient supply chains. In this scenario, productivity gains are inhibited, spoiling advancements in our living standards, impeding a faster decline in the “inflation” rate.

Ergo, entrepreneurs turn more discouraged to invest in new or improving existing technologies, correcting processes or simply creating more stuff and hire more workers. Furthermore, individuals in general have less opportunities for work in a less dynamic labour market, which hampers their standard of living in a material way, although it also demoralises them. For that reason, keeping the US constitution as a reference, Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness is severely frustrated.

Because of its nature, “inflation” is transitory. Indeed, prices can only stick with its ascension at ever increasing rates if demand outpaces supply at a continuously faster pace. Nevertheless, this imbalance will ultimately reach a breaking point, just as it happened in 1982, when the Great Inflation culminated in a double-dip recession in the US and several other crises throughout the world.

Alternatively, a country may lose its ability to pay its obligations, having a unique solution: austerity. However, there are two roads that are extremely destructive and which lead to the same destination. Either it opts to devalue its currency or accruing even more debt. The former leads directly to very high inflation or even hyperinflation if the ruler is incredibly thoughtless and foolish. The latter results in markets losing confidence in that country’s creditworthiness leading creditors to increasingly refuse to accept this country’s currency, ultimately ending up at the same place as the former. As reasoned on the post titled Putting the E in EM – the E is for Eurodollar, btw –, this could very well occur in emerging economies.

Despite all the alarmism and prattle, the truth is that prices are not about to spiral out of control at any moment. Perhaps in EE countries they are but not in AE ones. Obviously, this could change in the future, though, for the time being, no chance.

Those who claim the contrary, some have no clue what the eurodollar system is, others acknowledge their existence but have no idea how powerful and dominant it is, because they were not taught these in college, and the rest are merely imbeciles that are aware banks originate most of the debt but still affirm the central bank wizards make magic by pulling their levers.